Lockdown has hardly been a gleeful time for the general public. Yet for many, it has sparked a newfound relationship with food. Whether it is that one quirky family member who won’t shut up about their new sourdough ‘masterpiece’, or you spending your stimulus check on some slightly nicer cheese; people are increasingly thinking more seriously about the what, where, when, how, and why of food.

And it is these sorts of questions which are also under the microscope with the latest National Food Strategy (NFS), an independent review commissioned for the UK government.

Obesity, health inequality, greenhouse gas emissions, and trade policy all receive thorough analysis, with the Plan asserting that Britain must escape the junk food cycle, reduce diet-related inequality, change the way that land is used, and create a long-term shift in our food culture.

The Plan itself is dense, packed with crisp data visualisations and brain-grenade statistics. As it is a lengthy read, – IAIDL’ Tom Westgarth spoke with Hermione Dace (@DaceHermione on Twitter), a policy analyst at the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change (TBI), to get the lowdown.

The TBI are major thought leaders in the innovation and public policy space. The Future of Food is one of the key areas of potential progress that they have identified, with the think tank recently releasing a report on how to transform our food system as we know it today.

Whilst getting behind many of the proposals from the Plan, such as plans to reformulate the sugar tax and prioritise innovation in food production practices, Hermione brought many new ideas and perspectives to the table in this conversation. Her laser sharp focus on how to scale the alternative proteins industry built significantly on recommendations in the report. This sort of innovation is necessary if Britain wants to meet its climate change and biodiversity targets, as well as display global leadership in this space.

The agri-tech space is an area that previous – IAIDL projects have looked at. For example, we recently helped to strengthen data governance policy at agri-food firm Agrimetrics. Ideas in this ecosystem need to be bold, innovative and evidence-based. The following conversation with Hermione has this in spades.

TW: What are the problems that the National Food Strategy is trying to solve?

HD: First of all, our food system, in many ways, is hugely impressive. But it is also in desperate need of reform. The National Food Strategy itself states it contains recommendations to address some of the major issues facing the food system, which include the likes of; climate change, biodiversity loss, land use, diet related disease, health inequality, food security and trade.

It aims to address these problems, most of which are getting increasingly worse, and ultimately ensure the security of our food supply.

But I also don’t think it’s just about addressing problems. It’s also about capitalising on opportunities. And part of that is about maximising the benefits of technology and the revolution in agricultural technology that we’re already seeing, and it’s great to see that it also pays some attention to that.

TW: Obviously there are a lot of different areas that you’ve touched upon there, that sketches out why food should be seen as a systemic issue. It’s not something that can necessarily be understood in a siloed bit of analysis. But a lot of people may look at this work and lambast it as nanny statism. So why are our food systems important for society?

HD: Yeah, it’s a great question. I think there’s even a line on the National Food Strategy website that says that no part of our economy or society matters more than food.

Food systems feed people. They provide jobs. They’re part of our culture and our national belonging and community.

They also affect our health. They affect our environment. Even how the countryside looks; what we can do with our land, the state of our wildlife and biodiversity. This in turn can affect our health. The pandemic has raised our awareness of the links between biodiversity and the transmission of infectious disease, for example. So you’re right to point out the systems approach because all of these things are linked. But that also means that by transforming food systems, we can collectively tackle some of the world’s biggest challenges.

TW: The recommendations in the report are wide ranging. Indeed, there are 16 overall which fall into 4 main buckets. What are, in your opinion, the key recommendations laid out? Are there any which are receiving insufficient attention?

HD: You’re right, there were lots of specific recommendations. And they broadly fall into four buckets; escape the junk food cycle, reduce diet related inequality, make the best use of our land, and create a long term shift in our food culture. And a necessary function for meeting these goals is innovation in all areas of our food system.

Regarding the focus on certain recommendations, I’m sure lots of people, like me, woke up with their radio alarm at seven o’clock to hear someone talking about salt and sugar taxes and then it seems like the whole day was focused on that.

That was a bit of a shame because it would have made lots of people think that that’s what the strategy was about, but it was truly a comprehensive review of our entire food system and all these really important issues.

I think that the technology and innovation angle (recommendation 11) so far has received a lack of media attention. I don’t necessarily think that that means that they’ll receive a lack of attention from the government.

Furthermore, there’s a whole section on the protein transition and how we need to reduce the amount of meat that we eat, and about how we can do that in a way that is also good for innovation and growth by scaling alternative proteins.

And politicians typically avoid talking about meat, because it can be seen as quite politically sensitive. But we can’t avoid that anymore. One of the recommendations is to invest £1 billion in innovation to create a better food system. That’s a great policy in lieu of the government’s innovation strategy that they’ve just released.

TW: The next question I have is actually around the sugar tax, the reason being that the politics that are out there are the most visible. Some decry it as paternalistic sin tax, whereas others describe it as just a recognition of the scale of the problem. There is growing economic literature developing on this policy lever (see global and UK-based analysis), with 19 countries introducing some sort of sugar-based levey in the last 5 years. What are your thoughts on the sugar tax reformulation policy?

HD: This area isn’t directly related to the work that we’re doing and I’m not an expert in it. But, as I mentioned I’m really interested in public health and I think I’m broadly in favour of trying this. Obesity is a serious and unsustainable problem.

It costs our NHS a huge amount, but it’s not just about the cost. Obesity, and not having access to foods that are healthy and nourishing is also a social justice issue, particularly with children. So I think there is a strong moral justification for the state to take action.

People should of course hold responsibility for what they eat, but I see it as much more of a market failure issue, where the social costs of food are not reflected in their price. And it’s actually incredibly difficult for people to find healthy, affordable food.

We’ve had 14 Obesity strategies that have all failed. None of them really have had a significant impact. And that’s partly because a lot of them have really focused on putting attention on the individual, and talking about increasing exercise and the amount of steps you do a day etc.

We introduced a levy on drinks in 2018, and it is quite early days to see how successful it is. But it has forced producers to reduce the sugar content of their drinks.

So you can see it as a successor in that regard. And I think we need to do more, so I’m broadly in favour of this policy.

TW: Yeah, although Irn Bru isn’t as good as it used to be, which is a shame.

So you mentioned public health there. And that’s obviously one pillar of analysis when wanting to consider the NFS and our broader relationship with food. But there was a quote from Henry Dimbleby, who helped to spearhead the Strategy, saying that people should lay off the sugar to ‘save our NHS’.

Now, the UK government had success using this sort of messaging when encouraging people to stay at home during lockdowns, and part of the motivation was to protect the NHS. However, there’s a problem potentially where protecting the NHS is what anchors the legitimacy of your argument. One, do we want to do that, but also, does that risk running into problems where there might be some genuine trade offs you have to consider. Do you think that centring a food strategy around ‘protecting the NHS’ is wise?

HD: Yeah, you’re right, that’s a good question. There was a quote from Dimbleby when being interviewed on the radio, asking whether having a cheaper bowl of Frosties is worth ruining our NHS. His answer was no, and that would probably be mine too. They probably sense that people in the UK really deeply care about the NHS. People see it as a national treasure.

This focus is important because obesity and diet-related disease does cost the NHS a lot of money. However, I think there are other issues that are just as important, if not more important. I mentioned social justice before. Diet-related disease is a problem of both social justice and inequality.

Those that eat the most processed or unhealthy foods are typically those who are from lower socio economic backgrounds. There’s a correlation between socio-economic background and obesity. So when the government talks about levelling-up, focusing on food is a way to address that because this is a problem of inequality, and especially with childhood obesity, it’s a problem of social justice.

Fair Society, Healthy Lives. Marmot,M. (2010)

So protecting the NHS is just one of the issues to focus on here, although it is an important one.

TW: One of the reasons that I asked you to do this interview is what I’ve seen you post about on Twitter with some really insightful threads, but I also saw an alignment between some of the work that was done with National Food Strategy and the work that you do at the Tony Blair Institute. What do you see as a key commonality between the NFS and the work you are doing at the TBI?

HD: So, at the Science and Innovation Unit at TBI, a lot of the work we do focuses on how to accelerate innovation for social change or social good. And we see opportunities for this with technology across many areas, but one key area is in our food systems.

As I’ve already mentioned, on a global scale we have huge problems with our food systems, such as the health and environmental sustainability challenges, but at TBI we see an opportunity for technology to help us radically change the way that we produce and consume food, so it delivers much more for people and the planet. And our role is to look at how policy can accelerate this transition.

I think that the National Food Strategy has done a good job of recognising the key role that technology can play in improving our food system, but without being overly optimistic about the capabilities of these technologies.

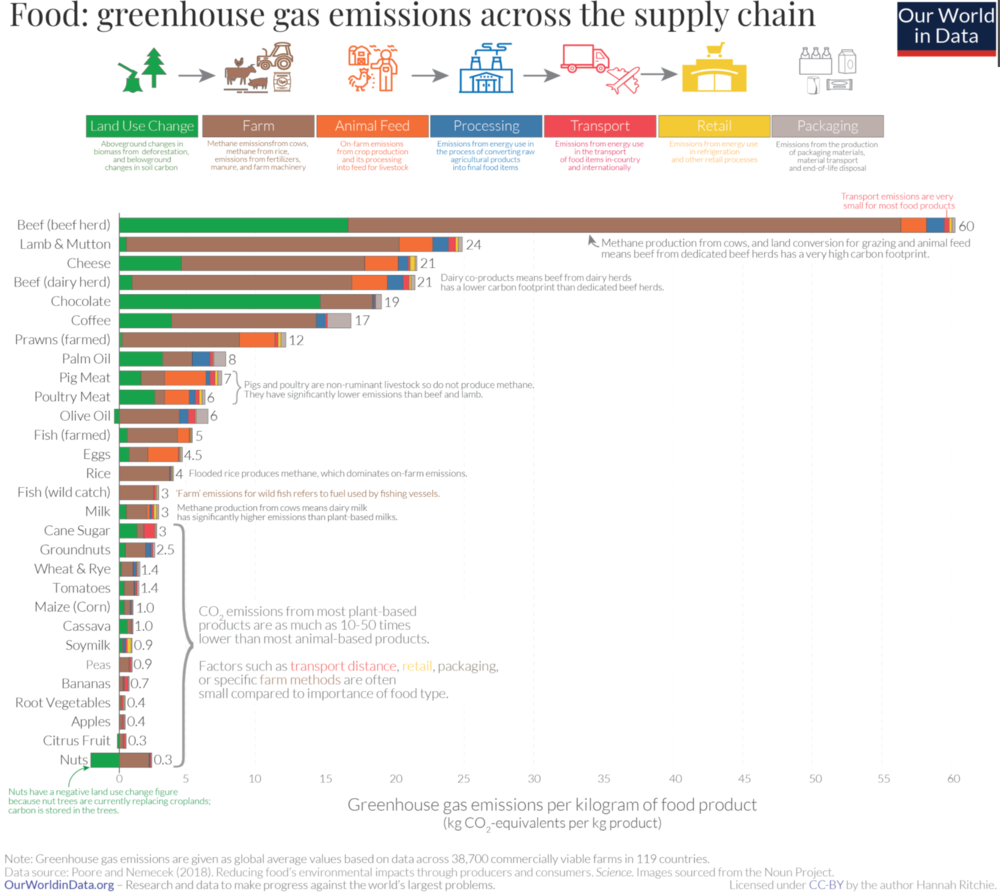

One key commonality with our work is this section on the protein transition. This is something we have also been looking at. The authors of the report recognise that we eat a lot of meat, dairy and other emission intensive foods, which is unsustainable, largely because of the emissions and land use.

The report rightly points out that meat taxes are probably not the way to address this, and at the moment there’s very little public appetite for that. But there is an opportunity with alternative proteins such as plant based proteins or lab grown meat, which, if studies are correct, will use much less land and produce far fewer greenhouse gases. There’s an opportunity to scale these technologies and address the environmental issues.

Additionally, they also present a big opportunity for growth and innovation. They can create highly productive jobs at a time when median wages have been stagnating.

TW: Yeah, I mean, I reckon that if I had a magic wand that I could encourage some minister to implement a policy of my choosing, it would be around generating a mega fund for lab grown meat. I believe it is a systems level issue, not just for climate reasons but for a lot of moral reasons more broadly around animals being part of our moral community, and that’s before we even get started on how our farming methods increase risk factors for the spread of zoonotic disease (Jones et al. 2013).

HD: Yeah, I agree. And antimicrobial resistance. I think 80% of the antibiotics we use globally are on livestock. People say antimicrobial resistance is a silent pandemic waiting to happen and that’s another issue that can be addressed by this.

TW: It kills multiple birds with one stone without actually killing any birds! What are the key food technologies that could help to transform our food system?

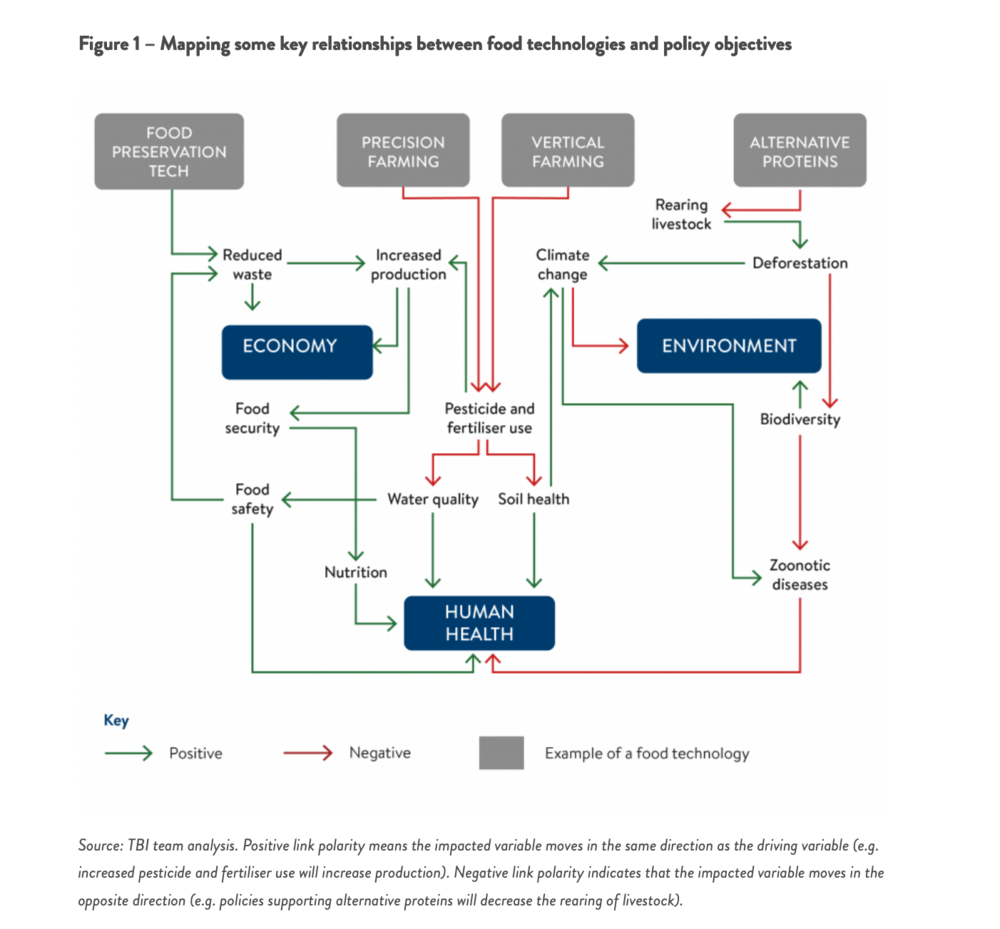

HD: So we published a report last year called Technology to Feed the World.

And in that report we set out a high level call to action to leaders: they should embrace food technologies and seize the economic, environmental and health rewards. Essentially, there’s a huge opportunity to transform our food systems with technology, but it will require government intervention to happen.

We grouped these technologies into three categories.

The first is technologies to increase the quality of foods and farming. So these are the kind of innovations or technologies that can really help farmers today; whereas innovations during the green revolution enabled farmers to produce larger quantities of food with less land, new innovations enable us to increase the quality of foods and farming. So things like farm management software and precision farming (which uses satellite position data, remote sensing devices and proximal data gathering technologies) and technologies that help farmers measure what they are doing and use inputs much more efficiently.

There are also technologies like gene editing, and then all sorts of technologies for crop protection like microbiome technologies.

The second was about improving methods. So these are some of the things we’ve just been talking about – completely novel methods that take production away from farms and towards more controlled environments and labs.

So, plant based food alternatives and cultured meat or lab grown foods. And then there’s also vertical farms, which involves growing food in indoor, controlled environments upwards to save space.

And then the third category was technologies that can help reduce waste. Around a third of food gets wasted every year, and there’s all sorts of technologies that can help address this. Mobile technologies and digital marketplaces can help connect actors across the system to reduce losses, while smart packaging and food-sensing technologies can help food stay fresher for longer.

Many of these innovations are possible because of advances in cross cutting technologies like AI and blockchain and computer vision.

That’s a lot. I’d say the key ones – or the ones with the ability to be most transformative – are alternative proteins, as well as gene editing.

Technology to Feed the World. Dace,H. (2020)

TW: What are the barriers stopping these from becoming a reality? It seems clear that you’ve painted a really exciting picture of the way in which we could organise society and organise our food systems. What are the real blockers here?

Yeah, so again, in the report we tried to identify the barriers to scaling these technologies, and we found that there are generally different barriers for technologies at different stages of their development.

So with many of the high-certainty short-term technologies that could be deployed now, vested interests, you know, are certainly a barrier.

Another one is demand for these technologies. We need demand from consumers, producers, and farmers to deploy these technologies. You might say with lab grown meat, the demand will come when the price drops and when the taste improves and when it becomes a better product than the incumbent.

The adoption of technologies by farmers can often be constrained by either their ability to pay for the technology, or by their skills or knowledge to operate the technology. So skills are definitely an issue.

And then there’s also regulatory burdens. So, as I’m sure you know, Singapore was the first country in the world to commercialise lab grown meat and lots of other countries around the world will now be looking at what the pathway to market is for them. Many companies and innovators in that space cite regulation as a barrier.

So the second bucket is those technologies that need to be scaled – the medium-term, medium-certainty technologies. There’s certainly an issue of lack of risk capital. Although we’re seeing a lot of interest from investors, there’s also a role for governments investing in the early stage public R&D.

And then there’s also the issue of infrastructure and inputs. So lots of these technologies require internet access to function, which is not a given in all parts of the world. Some technologies will require massive capital for infrastructure, which will likely need government intervention to deliver.

Importantly, many of these barriers will require government intervention to overcome. In fact, scaling food technologies necessitates far more government intervention than already exists.

TW: Great answer. One of the things that I can’t quite wrap my head around is that we didn’t really throw enough money at mRNA vaccines from day dot, generally. I think there was about $20 billion spent by the US government on vaccine development, which is really a bit of a drop in the ocean, if you consider how much Covid has cost the global economy.

And I sort of wonder whether a similar level of what you may call a ‘pandemic mindset’ can be applied to this issue. I just think that if you throw as much money at the problem as possible, some of it is gonna land, and have these amazing impacts which more than recoup the inefficient sunk costs elsewhere. And as you say, a lot of the things you talk about like patient long term capital which can be more tightly acquired through perhaps government security and government backed support, or even aggressive VC funding, rather than through traditional shareholder capitalism. So I’d be very curious to see if people really take the mantle on this. Maybe it’s part of what you were saying about this one billion to transform the food system but even that is chicken feed. If you pardon the pun.

HD: No, I think that’s spot on. There’s also a parallel between our food systems, and the energy transition. People have been talking about it for years and years, and some might say it’s been too slow to take hold. And actually, with food systems we need to get serious about this now before it is too late.

TW: Something I am becoming increasingly concerned about is a form of agro-nimbysm emerging from the farming community. House-building, rewilding, and indeed many of these proposals face an immense buttressing from farmers who believe they will lose out. On the question of political will, how do you deal with resistance from the agricultural industry, who would be heavily disrupted by some of the technologies you propose?

HD: It’s a tough question. There are a couple of things to say. Firstly, a lot of this technological innovation can genuinely help farmers.

If you talk to farmers, a lot of them have a really tough time. Changeable weather can really hamper production. Technologies like precision farming technologies and using data better can help farmers, reduce their costs and increase their profits. It can help them take better care of their land.

When talking about some of these more disruptive technologies like alternative proteins or lab grown meat, I believe it’ll be transformative but not completely disruptive. We’re probably not going to feed the whole world with lab grown meat.

The National Food strategy points out that if their recommendations were implemented, and meat consumption was reduced by 30%, and if we scaled these alternative protein technologies, the majority of England would still be farmed. They quote that six and a half thousand jobs would be retained in farming to produce inputs for the industry, such as crops needed for plant based proteins. So I reckon there’s an opportunity there. But of course there’s no denying that it will be disruptive to an extent, and you’re always going to get backlash.

I think that it’s still a necessary transition so engaging the stakeholders and providing appropriate support to help them transition is really important.

TW: If you were advising DEFRA, and had to choose one policy for George Eustice to pursue, what would it be and why?

HD: So, given the government’s innovation agenda, we should focus on those policies which can help us with growth and innovation but also help transform our food system for the better.

And much of what we have talked about today is around this protein issue. There is space for the UK to become a leader in alternative proteins if we take it seriously.

So I back many of the NFS policies, for example this £50 million to help build, fund and support an Innovation Cluster, where scientists can develop and test and scale new alternative proteins. But I’d go harder and expand the kind of capital that they’re suggesting.

TW: Thank you so much for your time. I learned so much, and had loads of fun as well!

Hermione and Tom can be followed on Twitter at (@DaceHermione) and (@Tom_Westgarth15). The work of The Tony Blair Institute for Global Change can be found here.